Celebrated with joy and reverence, Shabbat stands as a sacred retreat from worldly concerns. This day honors the Divine covenant with the Israelites, offering spiritual renewal and deeper connection with God. Rituals like candle lighting, Lecha Dodi, and Kiddush elevate Shabbat’s holiness.

זָכוֹר אֶת־יוֹם הַשַׁבָּת לְקַדְשׁוֹ

“Remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy”

Sanctity of Shabbat

In Judaism, it is called “Shabbat” (שבת), but in English, it is translated to “Saturday”. Shabbat, however, is a holy day in Judaism, dedicated to resting, signifying the seventh day of creation, and the fourth commandment of the Ten Commandments revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai as a Divine decree. Furthermore, it stands among the three covenants that God established with the Israelites following their exodus from Egypt.

Significance

Shabbat’s holiness holds a central place in Jewish belief, making it one of the most essential cultural and religious principles, with a distinguished place within the Jewish spiritual heritage. The Torah, in the Book of Genesis (Sefer Bereshit) Chapter 2, the Torah states that the heavens, the earth, and everything related were completed in six days. God completed His work on the seventh day, ceasing from all the labor He had undertaken. He then blessed the seventh day and made it holy, because it was the day that He had completed everything related to the creation.

The Book of Exodus (Sefer Shemot), Chapter 31, reinforces this by instructing believers to “Remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy”, establishing Shabbat as an eternal covenant, a sign between God and the children of Israel to be upheld throughout the generations.

Jews fulfill the commandment of Shabbat by performing rituals that affirm the Divine sovereignty and promote peace, health, and blessings throughout the world. They believe that on Friday evening, the Angel of Good Deeds accompanies those who cease from work and return to their homes for religious observance. This angel bestows blessings upon any household where the Shabbat candles are lit and the lady of the house has completed the preparations to welcome the guests, the family, and the Shabbat ceremony. The angel seeks Divine favor for the home to remain a place of joy and well-being.

The Sabbath, therefore, represents a pillar of Jewish faith and tradition, serving as both a spiritual retreat from material concerns and a means to nurture the soul and body.

Purpose

By observing Shabbat, the Jewish people separate themselves from worldly distractions, taking meaningful steps toward spiritual growth and inner completeness. It is a time set aside for physical and spiritual rejuvenation, preparing the faithful to face future trials with renewed vigor.

The reality is that during the week, life and its complications leave little room for self-contemplation or the pursuit of higher purpose. This is where Shabbat comes into play. This holy day offers a vital opportunity to rediscover one’s true identity and essence. It is a time where, as far as Jewish sages are concerned, reflects humanity’s ultimate destiny, where both body and soul can absorb the energies of love and peace. It is seen as a moment not only for self-awareness but also for deepening one’s connection with the Divine.

Grand Meal and Singing

As Friday approaches and the sun sets, Jewish families make arrangements for a grand meal to honor Shabbat. They prepare the finest delicacies and fruits, cleanse themselves, and don their best clothing. At synagogues, they gather to welcome Shabbat by singing the sacred hymn “Lecha Dodi”, composed by Rabbi Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz, a prominent 16th-century Kabbalist. Lecha Dodi is a heartfelt song that embodies the Jewish spirit of greeting Shabbat. In this song, Shabbat is poetically portrayed as a beloved bride, capturing the deep reverence and joy associated with its arrival.

לְכָה דּוֹדִי לִקְרַאת כַּלָה פְּנֵי שַׁבָּת נְקַבְּלָה

Lecha Dodi

Lecha Dodi, one of the most celebrated poems written to welcome Shabbat, was composed by Rabbi Yehuda Halevi Alkabetz, a distinguished Kabbalist of the 16th century. Originating from Thessaloniki, a city in present-day Greece, Rabbi Alkabetz later settled in Safed (Tzfat), located in northern Israel. He soon became an influential figure in the mystical community of the city. His spiritual hymn, Lecha Dodi, resonated profoundly with Jewish communities across the East and West, eventually becoming an integral part of the Friday evening prayer service. The hymn vividly expresses a Jew’s heartfelt emotions and serves as a poetic invitation to Shabbat, which is lovingly compared to a cherished bride. The poem follows:

Come my Beloved Friend to greet the bride, let us welcome the Sabbath.

“Preserve” and “Remember” in a single utterance the One Almighty caused us to hear; Adonoy is One, and His Name is One; for fame, for glory, and for praise.

Come my Beloved Friend to greet the bride, let us welcome the Sabbath.

To greet the Sabbath, come let us go for it is the source of blessing; from the very beginning, of old, it was appointed; last in creation, first in [God’s] thought.

Come my Beloved Friend to greet the bride, let us welcome the Sabbath.

Sanctuary of the King, royal city, arise, come forth from the upheaval; too long have you dwelt in the valley of weeping; He will show you abundant pity.

Come my Beloved Friend to greet the bride, let us welcome the Sabbath.

Shake the dust off yourself, arise, dress up in your garments of glory, my people; through the son of Yishai the Bethlehemite, draw near to my soul and redeem it.

Come my Beloved Friend to greet the bride, let us welcome the Sabbath.

Wake up! wake up! for your light has come, arise and shine. Awaken! awaken! utter a song, The glory of Adonoy is revealed upon you.

Come my Beloved Friend to greet the bride, let us welcome the Sabbath.

Feel not ashamed or humiliated why are you bowed down, why do you moan? In you will take refuge the poor of my people; and the city will be rebuilt on its ancient site.

Come my Beloved Friend to greet the bride, let us welcome the Sabbath.

They will be ravaged, those who ravaged you, and they will be cast far off, all who devour you. Your God will rejoice over you as a bridegroom rejoices over his bride.

Come my Beloved Friend to greet the bride, let us welcome the Sabbath.

Right and left you will spread out. and Adonoy, you will praise; through the man descended from Peretz we will rejoice and exult.

Come my Beloved Friend to greet the bride, let us welcome the Sabbath.

Come in peace, crown of her husband, come rejoicing and with good cheer; amidst the faithful of the treasured people. Come Bride, come Bride, come Bride, Shabbos Queen!

Come my Beloved Friend to greet the bride, let us welcome the Sabbath.

Creation and Sanctity of Shabbat

Divine creation

According to the verses of the Holy Scriptures, God created the heavens, the earth, the universe, and all its elements over six days. On the seventh day, He spread tranquility across the world, blessing and sanctifying that day to ensure that humanity recognizes the splendor of creation and enjoys its pleasures.

Jewish sanctity

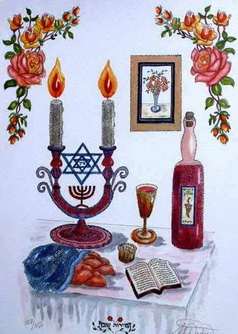

Jewish scholars uphold that Shabbat represents the pinnacle of creation. In honor of this sacred day, Jewish people engage in special ceremonies, approaching Shabbat with unique anticipation and joy. Traditionally, women perform the mitzvah of Shabbat by lighting the Shabbat candles and reciting the accompanying blessing just before sunset, marking the official beginning of the observance. This act is considered a significant and joyous occasion.

Shamor, Zachor, and Shalom Aleichem

Shamor and Zachor

Typically, two candles are lit, one representing “Shamor” (שָׁמוֹר) or “to keep”, and the other “Zachor” (זָכוֹר) or “to remember”. These symbolize the Divine presence (Shechinah) and emphasize the fourth commandment on the Tablets of the Ten Commandments: “Remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy”. After lighting the Shabbat candles, the following blessing (Berakhah) is recited:

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה’ אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָׁנוּ בְמִצְוֹתָיו וְצִוָּנוּ לְהַדְלִיק נֵר שֶׁל שַׁבָּת

“Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe, who has sanctified us with His commandments, and commanded us to kindle the light of the holy Shabbat”.

Shalom Aleichem

“Shalom Aleichem” is a greeting to the heavenly kingdom, inviting angels of peace to join the Shabbat celebration. Family members typically recite this welcoming prayer together, prior to the Kiddush blessing.

Kiddush

Importance

One of the essential Shabbat traditions is the Kiddush, which includes the Yayin blessing. This product is derived from grapes, one of the seven fruits blessed in Jewish tradition. Like bread, yayin is integral to religious ceremonies and festivals, consumed as a symbol of joy and spiritual delight. The production involves ten stages, just like bread, from the harvesting of grapes to their final preparation. Kabbalists interpret these stages as corresponding to the ten Sefirot (Divine attributes) essential for achieving spiritual perfection (tikkun) or ascending to the realm of Divine manifestation, Azilut. The ultimate goal is to unite with the sovereignty of Malkhut. Every Jewish individual is encouraged to fulfill these commandments and pass through these stages to attain spiritual completeness.

Midrashic texts teach that each Jew must prepare their soul to become a vessel capable of receiving the Shechinah, the Divine light. This readiness enables one to embody holiness, uphold moral virtues, and establish peace and serenity within one’s life. By observing and sanctifying Shabbat, a person can fully embrace this Divine blessing.

Ingredients

For Kiddush on Shabbat, red yayin is traditionally used, symbolizing human desires and the energy of receiving. The primary condition for performing Kiddush is the existence of a strong, inherent desire within a person. In this context, the term “yayin” means “keli”, which means “vessel”, denoting human capacity and potential.

After six days of labor and honorable work based on ethical principles, Shabbat offers a time for spiritual reward and the fruit of one’s efforts. The activities and intentions maintained throughout the week prepare the soul, like a vessel (keli), to receive Divine wisdom and love as a precious gift from God.

Kabbalistic insight into yayin

The letters of “yayin” (יין) carry profound Kabbalistic significance. The letter י (Yod) symbolizes Shechinah, the light of Divine wisdom. The second י (Yod) represents “chesed”, or love and humanity. The letter ן (Nun) refers to “Sha’ar”, the fifty gates of understanding, signifying the soul’s ultimate spiritual journey.

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה” אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם בּוֹרֵא פְּרִי הַגֶּפֶן

“Blessed are You, God, our Lord, King of the universe, for the life-giving and the sustaining [food], for the vines and the fruit of the vine…”

Berakhah of HaMotzi (The Blessing Over Bread)

The tradition during Shabbat includes using two loaves of bread (challah) following the blessing of Netilat Yadayim (handwashing). This ritual commemorates the heavenly manna that descended to sustain the Israelites in the Sinai desert. By reciting the Berakhah of HaMotzi (a thanksgiving blessing), participants express their gratitude to the Creator and seek permission to partake in the world’s sustenance and other blessings.

The Torah mentions that the manna provided on Friday was twice the usual amount, with an extra portion reserved for Shabbat, emphasizing its sacredness. This ensured there was no need to gather food on this day of peace and completeness. Thus, the blessings of Netilat Yadayim and HaMotzi signify the protection and nourishment of the body to uphold spiritual acts such as righteous thoughts, deeds, and words.

Netilat Yadayim

بָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה” אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם אֲשֶׁר קִדְּשָׁנוּ בְמִצְוֹתָיו וְצִוָּנוּ עַל נְטִילַת יָדָיִם

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe, who has sanctified us with Your commandments, and commanded us concerning the washing of the hands.

Berakhah HaMotzi

בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה ה” אֱלֹהֵינוּ מֶלֶךְ הָעוֹלָם הַמּוֹצִיא לֶחֶם מִן הָאָרֶץ

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the universe, who brings forth bread from the earth.

Shabbat Meals

Using the best food

During ancient times, it was customary in the gatherings of nobles and dignitaries to serve esteemed guests with the finest dishes, including fish, meat, and soup. Since then, it has become an essential practice to prepare the best food for the Shabbat meal — even when eating meat is forbidden, it is permitted on Shabbat.

Fish

For many Jewish families, fish holds a special place on the Shabbat table, consumed along with a blessing. Aside from being a symbol associated with the Hebrew month of Adar, fish represents blessings, abundance, and the sustenance designated by God for His servants. It also symbolizes the elevation of the traits of a righteous or sincere individual. Because fish dwell in the depths of the waters, they remain hidden from the evil eye. Similarly, Shabbat is a source of blessing and abundance, possessing energies that protect against harm.

Numerical Significance

The meals, Kiddush, and Shabbat candle rituals hold significant Kabbalistic importance, as they are linked to the numerical values of words associated with Shabbat. Here are some key observations:

- The word “Ner” (נר, candle light) has a numerical value of 200+50=250, with the digits (2 and 5) summing to 7.

- The word “Yayin” (יין, wine) has a numerical value of 10+10+50=70, its digits (7 and 0) summing to 7.

- The word “Challah” (חלה, Shabbat bread) has a value of 8+30+5=43, its digits (4 and 3) summing to 7.

- The word “Dag” (דָג, fish) equals 4+3=7.

- The word “Basar” (בּשר, meat) has a value of 2+300+200=502, with the digits (5 and 2) summing to 7.

- The word “Marak” (מרק, soup) has a value of 100+200+4=340, its digits (3 and 4) summing to 7.

- The word “Orez” (אורז, rice) has a value of 200+7+6+1=214, its digits (2, 1, and 4) summing to 7.

Clearly, the items used on the seventh day (Shabbat) hold significant importance, as the numerical values of every single one — Shabbat candles, wine, challah, fish, meat, soup, and rice — add up to seven. This number symbolizes the unique energies and spiritual qualities connected to Shabbat, since in Jewish tradition, the number seven is not only considered sacred and complete, but is also rich with symbolic meanings. These include the seventh day of the week (Shabbat), the seven Sefirot (Divine attributes), and Malkhut (kingdom), among others.

Birkat Hamazon (Grace after Meals)

Birkat Hamazon (Grace After Meals) is a heartfelt way of expressing gratitude for God’s kindness and acknowledging the blessings we have enjoyed.

Jews observe Shabbat by resting from material concerns and creating a peaceful, spiritual atmosphere through prayer and studying sacred texts, either at home or in the synagogue. As dusk approaches, they recite the afternoon prayer Mincha, followed by Arvit, and then end Shabbat with the Havdalah blessing, bidding farewell to this special day with solemn reverence.

They draw on the blessings and sacred energy of Shabbat to spiritually strengthen themselves for the week ahead, helping them fulfill their responsibilities successfully. They then eagerly anticipate the arrival of the next Shabbat, looking forward to experiencing this Divine presence once again.

Observance of Shabbat in Ancient Times

Before and after exile

During the time of the Beit HaMikdash (Holy Temple), it was customary to prepare for Shabbat by filling and lighting the large menorah with special oil before sunset. Twelve loaves of challah bread, symbolizing the twelve tribes of Israel, were placed at the base of the menorah. During the exile following the destruction of the Beit HaMikdash, Jews, who were scattered across the diaspora, would visit prophets on Shabbat to gain inspiration from their teachings.

Musaf service

The musaf service on Shabbat refers to the offerings made at the Beit HaMikdash, which included two unblemished year-old lambs, two-tenths of an ephah of fine flour mixed with oil, and wine, all presented as burnt offerings.

Announcing Shabbat

In the early first century, the approach of Shabbat was announced by sounding the shofar six times at set intervals. The first blast signaled farmers to stop working and head home. The second blast instructed merchants to close their shops, and the third reminded women to light the Shabbat candles. Finally, three concluding blasts signified sunset and officially marked the beginning of Shabbat. In certain parts of the Holy Land, this tradition of announcing Shabbat with the shofar is still observed today.

Shabbat’s sanctity is so deeply revered in Jewish life that during the oppressive reign of Antiochus IV, Jews chose death and suffering over violating its holiness. Eventually, Jewish sages permitted self-defense on this sacred day.

Shabbat in Other Faiths

More than 3,300 years later, many non-Jewish communities around the world, believed to have Jewish ancestry, continue to honor Shabbat traditions. They light two candles before sunset and perform rituals in a spiritual observance free from superstition.

While sanctifying Shabbat is a core religious duty for Jews, the spiritual act of lighting Shabbat candles has influenced followers of other faiths. This ancient tradition continues in various ceremonies, both religious and secular, for joy or sorrow, fostering a serene and spiritual environment.

Shabbat According to Kabballah

Kabbalistic teachings convey that women and Shabbat reflect one another. The Hebrew term Shabbat (שבת) consists of two components: ש (Shin), representing the Creator and derived from Shaddai (שדי), a foundation in creation, and בת (Bat), meaning daughter or Lord.

Shin has a numerical value of 3, and is formed from three connected letters “ו” (Vav), each symbolizing one of the three Sefirot or Divine attributes:

- Chesed (חסד), associated with Abraham, representing love and kindness.

- Gevurah (גבורה), linked to Isaac, signifying discipline and strength.

- Tiferet (תפארת), related to Jacob, symbolizing harmony and balance.

The other part of the word, “בַּת” (Bat), translates to “daughter” or “Lord” and is derived from the term “בַּתוֹלָה” (Batulah). The numerical value of Shabbat is 702. If we ignore the zero in Shabbat’s numerical value, 702, we get 72, which is the number of God’s names. God has 72 names.

Additionally, Shabbat’s numerical value is the same as Tikrat (תקראת), meaning conflict. These two are two opposing poles, which symbolizes that neglecting Shabbat invites strife, whereas observing it brings about peace and harmony.

Rearranging the letters of Shabbat (שבּת) forms the word Bosheth (בשת), meaning shame, emphasizing that neglecting Shabbat leads to dishonor. Additionally, rearranging the letters of Shabbat brings about a different word that implies that Shabbat is the best day to recognize one’s errors by engaging in religious rituals and studying the Torah.

Shabbat, akin to Brit Milah and Tefillin, represents one of the Divine covenants between God and Israel.

Brit Milah: This is a sacred, engraved covenant symbolizing a spiritual bond with God.

Tefillin: Signifies liberation from Egypt.

Shabbat: This covenant creates a direct connection between the soul (Neshamah) and God, guaranteeing to achieve this through the shortest path. By observing and honoring Shabbat, a person achieves spiritual healing (Tikkun), linking their soul to the Divine realm of Azilut.

It is said that a Greek scholar once claimed that Jews rest one day a week to work better during the other six. In response, one of the rabbis explained that he was mistaken and that the opposite was true. Jews spend the six days of the week living with spiritual awareness, so they can fully experience the Divine wisdom of Shabbat and ultimately unite with God.

Important Shabbats of the Year

Shabbat Shuvah (שבת שובה)

Shabbat Shuvah, the Shabbat before Yom Kippur, is when spiritual leaders encourage the community to repent and change their actions and negative traits from the past year.

Shabbat Shirah (שבת שירה)

Shabbat Shirah commemorates the miracle of the Red Sea splitting and the drowning of Pharaoh’s forces as the Israelites escaped from Egypt. The Song of Gratitude, Az Yashir, is sung in celebration.

Shabbat Shekalim (שבת שקלים)

Shabbat Shekalim is a special Shabbat focused on collecting offerings for the Temple, used as sacrifices throughout the year.

Shabbat Zachor (שבת זכור)

Shabbat Zachor is observed on the last Shabbat before Purim. It includes reading Torah verses that recall God’s dislike for Amalek, a nation symbolizing blasphemy and enmity.

Shabbat Parah (שבת פרה)

Shabbat Parah focuses on the ritual of the Red Heifer, which was sacrificed and burnt in the Holy Temple. Its ashes were used to purify the pilgrims of the Temple and the dead of their sins.

Shabbat HaGadol (שבת גדול)

Shabbat HaGadol, the Shabbat before Passover, marks the last Shabbat the Israelites spent in Egypt and remembers the miracle that prevented Pharaoh from executing his plan to attack them.

Shabbat Rosh Chodesh (שבת ראש חדש)

Shabbat Rosh Chodesh is when the new month starts on Shabbat. Special religious ceremonies are performed on this day.

Shabbat Machar Chodesh (שבת מחר חדש)

Shabbat Machar Chodesh happens when Shabbat falls the day before the new month. The Haftarah of Machar Chodesh is read in a special ceremony.

Key Aspects of Shabbat

- Three sacred covenants bind God to the Children of Israel: Brit Milah (circumcision), Shabbat, and Tefillin. These commitments represent a deep spiritual connection in Jewish tradition.

- Seven parashot in the Torah emphasize the importance of observing Shabbat and following its laws:

- Beshalach

- Yitro

- Mishpatim

- Ki Tisa

- Vayakhel

- Emor

- Va’etchanan

- Lighting Shabbat candles symbolizes the separation of Shabbat from the other days of the week. Reciting Shalom Aleichem (שָׁלוֹם עֲלֵיכֶם) on Shabbat evening brings peace and invites the Divine presence of the Shechinah (God’s light) into the home for the coming week.

- Shabbat rituals include lighting candles, reciting Shalom Aleichem, blessing the wine (Berakhah Yayin), performing handwashing (Netilat Yadayim), blessing the bread (HaMotzi), sharing festive meals (Seudot), reciting Birkat Hamazon (Grace After Meals), praying (Tefillah), studying Torah, and concluding with the Havdalah blessing.

- The sanctity of Shabbat is so great that the mitzvah of Tefillin is not performed on this day.

- During Shabbat’s Torah reading in the morning, seven blessings are recited. In the afternoon Mincha service, three blessings are included.

- Newborns are usually named on Shabbat in the presence of the Torah.

- A groom or father of a newborn son is summoned to read and hear the parashah of the Torah.

- The Berakhah Gomel (גּוֹמֵל) is recited in the presence of the Torah in gratitude by those who have recovered from illness, evaded a danger, returned from long travel (by air or sea), or been freed from imprisonment.

- Psalm 121 is recited for the sick, captives, or anyone facing danger, asking for Divine intervention and safety.

- Those who have lost a loved one and are observing an anniversary for them recite the Maftir or Mishnayot blessings along with Kiddush, thereby fulfilling their obligation, while the congregation offers its respects.

- The Talmud (Gemara Shabbat 119b) explains that one reason for the Temple’s destruction was the desecration of Shabbat.

- Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai stated that if the Jewish people were to observe two Shabbats as commanded, God would bring their salvation.

References

- Torah

- Talmud

- Gemara

- Ari HaKadosh

- Mythological Beliefs, Yosef Setareshenas

فارسی

فارسی