Farsihud, Persian written in Hebrew script, captures centuries of Iranian Jewish history, philosophy, and artistry. From ancient inscriptions to epic poetry, these texts reveal the intersection of Persian, Jewish, and Islamic cultures. Persian Jews documented their unique heritage while contributing to Persian literary traditions, with influential figures from Maimonides to Ferdowsi shaping their works.

The term Farsi-Yahudi, or Farsihud, refers to both the Jewish dialects spoken by Iranian Jews and the Persian texts written using the Hebrew script.

Historical Background

Following the guidance of Rabbi Yossi (d. 323 AD) at the Babylonian Academy, Iranian Jews transitioned from speaking Eastern Aramaic, their language during the Talmudic era, to Pahlavi. Later, in the Islamic era, they adopted Persian Dari as their spoken language like the rest of the Iranian population. Linguistic evidence suggests that from the Abbasid period onwards, Persian Dari, also known as New Persian or “Farsi” in Arabic, became the language of communication for Iranian Jews.

History of Iranian Jews’ Writing

Despite speaking New Persian during the Islamic period, Iranian Jews chose the Hebrew script over the Arabic script for writing. Linguists call this form of writing Farsihud (Farsīhūd), and it represents some of the earliest documented examples of New Persian texts.

Earliest Farsihud Samples

As mentioned before, Farsihud refers to any Persian text written in Hebrew script. The earliest discovered examples of such texts are found on inscriptions, plates, metal artifacts, and a few letters and commercial contracts. Notably, two letters dating back to around 750-800 AD were found in Dandan Oilik, near Khotan in Chinese Turkestan. The first letter, now preserved in the British Museum, was discovered in 1901 by a team led by Aurel Stein. The second, known as the Khotan Letter, was discovered in 2004 near the same site.

The Dandan Oilik letter

The Khotan letter

Artifacts from this era also include several small inscriptions discovered in the Ozughan Defile in Afghanistan, which date back to approximately 752 AD. Another significant collection comprises documents found within the “Cairo Geniza,” a storeroom of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo. Notably, among these documents are two official records from Ahvaz, dating to the years 951 and 1020 AD. In recent developments, the Central Library of Israel announced its acquisition of several manuscripts from Afghanistan’s Geniza, sourced through reputable dealers. This collection, as described in current reports, primarily consists of writings from Jewish communities of the eleventh century residing along the Silk Road.

The presence of these artifacts indicates that, from the early centuries following the rise of Islam, Persian Jews inhabited this extensive region, actively participating in the preservation and enrichment of Persian culture and language.

Styles of Farsihud Writings

Farsihud writings encompass a broad range of styles, from classical literary texts to local dialects. These texts often incorporate three key elements—Judaism, Iran, and Islam—though the prominence of each depends on the type of writing. In literary texts, Iranian elements are most pronounced; in religious texts, Jewish themes dominate; and in philosophical or mystical writings, Islamic influences are more evident. These writings address religious, non-religious, scientific, mystical, historical, and everyday subjects.

Farsihud Readers

For centuries, the primary readers of Farsihud texts were Jews who were literate in Hebrew script but unfamiliar with Persian script.

Farsihud Writers

As time passed, writers of Farsihud were divided into two main groups. The first group consisted of those who had greater familiarity with Hebrew and used Farsihud primarily for translating religious texts and laws. The second group comprised writers who were not only familiar with religious text, but were also proficient in Persian language and literature. Their writings are generally clearer and grammatically more precise than those of the first group.

Cultural and Religious Influences on Farsihud Writers

Farsihud writers were often influenced by both non-Iranian Jewish and non-Jewish Iranian figures.

Influential non-Iranian scholars

Several respected names emerge among the non-Iranian Jewish scholars and philosophers whose works served as profound sources of inspiration for Persian Jewish writers,.

Moses ben Maimon, widely known as Maimonides, holds a place of particular significance. His ideas deeply impacted various Persian Jewish authors and poets, evident in works such as “The Thirteen Principles of Faith of Israel” by the Persian Jewish poet Imrani, written in 1508 AD in Kashan. His influence is also seen in the philosophical treatise “Duties of Judah” by the Iranian philosopher Judah ben Elazar, composed in 1686 AD in Kashan, as well as in “Hayat al-Ruh” (Life of the Soul) by the Jewish poet and thinker Simantov Melamed, who passed away in 1821 AD in Mashhad. Other influential non-Iranian scholars include Saadia Gaon, a rationalist philosopher based in Baghdad during the 9th and 10th centuries, Bahya ibn Paquda, a Spanish Kabbalist active in the late 11th century, and Judah ben Samuel ibn Abbas ibn Abon, a Spanish Jew who resided in Africa during the 12th century.

Influential Iranian non-Jewish figures

The Iranian non-Jewish poets and writers whose works left a lasting impact on Persian Jewish literature encompass a range of celebrated figures. Among these are Ferdowsi, Saadi, Rumi, Omar Khayyam, Jami, Nezami, Attar, Hafez, and Ubayd Zakani. Foremost among them stands Ferdowsi and his renowned work, the Shahnameh (The Book of Kings).

Value of Farsihud Writings

Farsihud writings hold various types of value, some of which include:

- Linguistic Value: Judeo-Persian writings are a crucial resource for tracking the evolution of Middle Persian (Sasanian Pahlavi) into New Persian. In his translated article, “The Dialectology of Judeo-Persian” (Padiavand, Vol. 1, edited by Amnon Netzer, Mazda Publishers, 1996), Professor Gilbert Lazard of the Sorbonne University in Paris emphasizes the linguistic and historical significance of these texts.

- Historical Value: The book Anusim, written by Babai ben Lotf and continued by Babai ben Farhad, with around two hundred additional verses by Mashiah ben Rafael, holds significant historical value. These works provide a lasting record of the lives and forced conversions experienced by Iranian Jews—a history that, aside from a few brief documents, has left little trace in other sources.

- Religious Value: The book Anusim, written by Babai ben Lotf and continued by Babai ben Farhad, with around two hundred additional verses by Mashiah ben Rafael, holds significant historical value. These works provide a lasting record of the lives and forced conversions experienced by Iranian Jews—a history that, aside from a few brief documents, has left little trace in other sources.

- Social Value: Farsihud writings reflect the integration of Iranian customs and Islamic culture within Jewish communities, while also expressing the marginalization experienced by Jews in broader Iranian society.

- Literary Value: Persian Jewish prose and poetry reflect the cultural and intellectual depth of Iran’s Jewish community. By comparing these texts with works by non-Jewish Iranian poets, readers can see the Jewish community’s understanding of rhetoric, meter, rhyme, and their skill with Persian vocabulary and grammar.

Classification of Persian Jewish Works

Persian Jewish literature has been categorized in various ways. Amnon Netzer’s classification includes:

- By Time Period: Either initiated before or after the Mongol invasions.

- By Style: Grouped into prose and poetry.

- By Content: Divided into religious and secular themes.

Gilbert Lazard, a French Iranologist, classified these works into four periods. Lazard’s first two periods align with the pre-Mongol era, while his third and fourth correspond to the post-Mongol period in Netzer’s classification.

First Period: 8th to 11th Centuries AD

In this era, dominated by Arabic cultural influence, the transition to New Persian appears in the writings of Iranian Jews and Zoroastrians. Early Islamic rule in Iran left only a few Persian Jewish works, mostly Hebrew texts by Iranian Jews. The surviving artifacts include some vessels, tombstones, inscriptions, and incomplete documents valued mainly for their religious and linguistic content rather than literary significance.

Second Period: 12th to 14th Centuries AD

Most works from this period are translations and interpretations of the Bible from Hebrew and Eastern Aramaic into Persian. Written in prose, these translations are kept in major libraries and museums worldwide, including Paris, London, St. Petersburg, and Jerusalem. Among the notable examples are a Persian translation of the Book of Esther from 1280 AD in Paris’s National Library and a translation (or commentary) of the Book of Ezekiel in St. Petersburg.

Third Period: 14th to 18th Centuries AD

This period marks the beginning of secular and non-religious writings by Iranian Jews, reflecting their cultural flourishing during the Middle Ages. The sack of Baghdad by Hulagu Khan in 1258 AD influenced the trajectory of Jewish life in Iran. Between 1258 and 1291, the Ilkhanid rulers’ lack of Islamic affiliation allowed non-Muslims, including Jews, greater freedom socially, culturally, and politically.

Key Persian Jewish poets of this period include Shahin in the 13th–14th centuries, Emrani in the 15th–16th centuries, and Baba’i ben Lotf in the 17th century. While secular literary forms were developing, translations and commentaries on religious texts continued to be produced.

Fourth Period: 17th to 19th Centuries AD

Works from this period largely originate from Greater Khorasan and regions beyond the control of the Safavid rulers. Under religious pressure during this challenging period, some Iranian Jews migrated to India and China, while many moved to Bukhara and nearby regions, where they continued to create literature in Persian and Tajik.

By the late 18th and 19th centuries, Jewish writers translated Persian classics, including works by Saadi, Hafez, and Jami, into Judeo-Persian. In the 20th century, as Persian language education became accessible through Alliance schools and later Iranian national schools after the Constitutional Revolution, the need to write in Judeo-Persian gradually faded. However, some older Iranian Jews still use this script for correspondence.

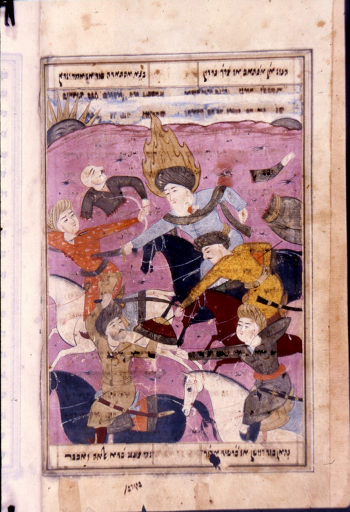

Example Scene from the Poem Yusuf and Zulaikha by Jami, Courtesy of Jewish Theological Seminary.

In this romantic verse, rewritten in Judeo-Persian by Mashhadi Jews in the 1850s, Zulaikha expresses her longing:

In this romantic verse, rewritten in Judeo-Persian by Mashhadi Jews in the 1850s, Zulaikha expresses her longing:

به هر ساعت فتاده پیش اویم

سرِ طاعت نهاده پیش اویم

“Every hour, I lay myself before him,

Bowing my head in obedience to him.

درون پرده کردم جایگاهش

که تا نبود به سوی من نگاهش

I prepared a place within the veil,

So his gaze would not turn my way.”

ز من آیین بی دینی نبیند

درین کارم که می بینی نبیند

You’ll see no lack of faith in my ways;

No trace of irreverence in all I do.

چو یوسف این سخن بشنید زد بانگ

کزین دینار نقدم نیست یک دانگ

When Yusuf heard this, he cried aloud:

“Not even a coin’s worth of this wealth is mine!

تو را آید به چشم از مردگان شرم

وزین با زندگان در خاطر آزرم

You shall feel shame before those who have passed,

And dishonored by those who still live.”

Persian Jewish Poetry: Styles and Themes

Persian Jewish poetry is classified into several styles and themes, including:

- Epic:

- Mythical Epics: Includes sections from Shahin’s Afarinesh Nameh (Book of Creation) by and Emrani’s Fath Nameh (Book of Conquest).

- Religious Epics: Encompasses works such as parts of Musa Nameh by Shahin, Fath Nameh (Book of Conquest) by Emrani, and Shofetim Nameh (Book of Shofet) by Ahron ben Mashiah.

- Historical Epics: Features works like Ardeshir Nameh (Book of Ardeshir) by Shahin, Daniel Nameh (Book of Daniel) by Khajeh Bukhari, and Hanukkah Nameh (Book of Hanukkah) by Emrani, which recount the Greek influence on Jewish culture before the birth of Christ.

- Historical Narrative Style:

- Works such as Anusim and the historical accounts by Baba’i ben Lotf Kashani fall under this category. These accounts cover the Safavid period, focusing on the reigns of Shah Abbas I and Shah Abbas II (1613–1660 AD). Later continued by his grandchild, or great-grandchild, Baba’i ben Farhad Kashani, these narratives extend up to Ashraf Afghan’s invasion, with around two hundred additional verses contributed by Mashiah ben Rafael of Kashan.

- Lyric Style:

- Emotional Poems: Includes:

- Excerpts from Yusuf and Zulaikha by Shahin in Afarinesh Nameh (Book of Creation);

- Verses from Saqi Nameh (Book of the Cupbearer) by Emrani, celebrating nature;

- Poems of separation and exile by Yusuf ben Eshagh, a Jewish poet.

- Mystical Poems: Includes:

- Sections from Saqi Nameh (Book of the Cupbearer) by Emrani;

- The Prince and the Sufi by Elisha ben Samuel (Raghib);

- Excerpts from Hayat al-Ruh (Life of the Soul) by Simantov Melamed (both verse and prose).

- Emotional Poems: Includes:

- Wisdom and Advice Style:

- Examples:

- Ganj Nameh (Book of Treasures) by Emrani, inspired by paternal advice or the Mishnah of Avot;

- The Thirteen Principles of Faith by Israel, composed by Emrani.

- Examples:

- Panegyric Style:

- This style is only represented by Shahin’s praise of Sultan Abu Sa’id (1316–1335), the Ilkhanate king, in the poetic work Ardeshir Nameh (Book of Ardeshir).

- Satirical Style:

- Satirical poems by Amina, which humorously convey his frustration with his wife and his general views on women.

Excerpt from Musa Nameh (Book of Moses),

Courtesy of Israel Museum.

Musa Nameh (Book of Moses), written by Shahin, includes a dramatic scene where Moses’ mother throws him into the fire to save him from Pharaoh.

چه چاره پس که چاوشان درآیند

بما یک دستبردی وا نمایند

“What else to do as the heralds approach,

And rob us all in one swift move?

به خانه در نبود آن لحظه عمران

به گِلکاری بود اوغمگین وحیران

While Imran was not home,

Busy working with clay, saddened and bewildered.”

Scene from the Fath Nameh (Book of Conquest) Epic by Emrani, Courtesy of Ben Zvi Institiure:

“Then the sun, commanded by God’s might,

Stood still in the sky, halting its flight.

The world shone bright because of the Sun,

Proclaiming God’s Greatness.”

From the Musa Nameh (Book of Moses) Epic by Shahin, about Moses Crossing the Red Sea:

“Every wall must be fully raised,

Standing latticed, perfectly arrayed.

So we can see each other’s faces there,

And choose the path we’ll each prepare.”

Scene from the Musa Nameh (Book of Moses) Epic by Shahin, depicting Balaam’s Death by Pinhas, Courtesy of Jewish Theological Seminary:

“Like a farmer sowing seeds on barren ground,

No profit, no harvest will ever be found.

Barren soil holds no worth, no gain,

Even if watered, no life it will sustain.

A flawed emerald keeps its flawed design,

Like barren soil, no goodness does it define.

Its tongue speaks only harm and spite,

Seeking only to wound, never to unite.

Balaam, though revered, was deeply flawed;

The gift of prophecy to him was but a fraud.

The Wedding of David and Abigail from Farh Nameh (Book of Conquest) by Emrani (Based on the Book of Samuel):

At dawn, like the Sun, he became a radiant groom,

Filled the world with a cup of golden bloom.

The bride, the moon, in her modest veil,

Filled the Sun with her warmth as she unveiled.

The groom called for the wedding feast,

And a new bride approached the honored seat.

From those close to him, loyal and dear,

They brought lavish gifts, sparing no cheer.

By Dr. Nahid Pirnazar, University of California, Los Angeles

فارسی

فارسی