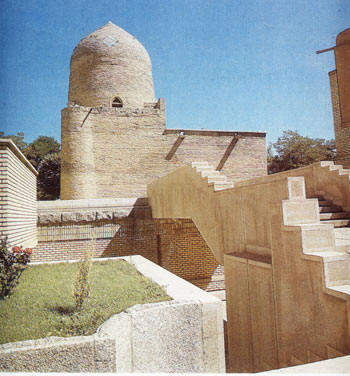

Exterior view of the shrine of Esther and Mordechai

To see 360-degree images (panorama) of Esther and Mordecai Shrine, please click

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

The First Jewish Migration to Iran

According to historical records and available evidence, the first migration of Jews to Iran occurred in 539 BC, following the downfall of the Babylonian Empire by Cyrus the Great. Within a short period, they settled in various parts of the country, concentrated in the western, central, and northern regions.

While precise data on the number and timing of Jewish arrivals in Iran and other cities remains unclear, it is undeniable that Iranian Jews hold a more significant historical legacy and cultural authenticity compared to other Jews who migrated to other parts of the world. Some trace their roots to the Tribe of Simeon (descendants of Jacob), while others claim lineage from King David, the father of Solomon.

Jewish Settlement in Hamadan

During the reign of Persian and Achaemenid kings, the city of Hamadan, also known as Ecbatana, was a prominent and popular summer resort, making it one of the most densely populated Jewish centers in Iran. In fact, in the past century, Hamadan’s marketplace was also known as the “Jewish Bazaar of Hamadan”.

The Tomb of Esther and Mordechai

Jewish significance

The Tomb of Esther and Mordechai in Hamadan holds immense significance as one of the most revered pilgrimage sites for Jews in Iran and around the world. Revered as saviors and prophets of the Jewish people, Esther and Mordechai have long been etched in the collective memory as legendary figures, playing a pivotal role in shaping and sustaining the presence of the Jewish community in Iran, particularly in Hamadan.

For many years, the Tomb of Esther and Mordechai has been recognized as a valuable piece of Iran’s cultural heritage. The tomb is within the ancient Jewish cemetery in the heart of Hamadan, at the beginning of Shariati Street.

History and architecture

The dome adorning the tomb reflects the architectural style of Islamic structures. Constructed in the 13th century (during the Mongol era) under the government of Sa’d al-Dowleh, the tomb was built with stones and bricks and upon an earlier edifice dating back to the 9th century (3rd century AH). For centuries, the surrounding land has served as a Jewish cemetery.

During the Qajar era, part of this cemetery was seized by one of the large landowners. Following a complaint by the community to Naser al-Din Shah and his intervention, another piece of land was allocated to the Jewish community of Hamadan for a cemetery on the other side of the shrine. Also, during the reign of Reza Shah, the cemetery was restricted in order to implement a street layout plan. Most of the cemetery was converted into a park.

The interior of the shrine consists of an entrance, a corridor, a tomb, an Iwan (a vaulted hall open on one side), and a Shah-Neshin (a raised platform designated for a prominent individual). Two exquisitely carved chests (marquetry) stand out in the center of a square room, on top of the two tombs.

Graves of Esther and Mordechai

The older chest, which is located on the south side, belongs to Esther. The sides of the chest are decorated with texts in Hebrew, containing information on the construction of this chest.

The second chest, which is almost similar to Esther’s chest, belongs to Mordechai and was made in the year 1300 by the great marquetry artist, Enayatollah ibn Hazrat Gholi Tuyserkani.

Above the tomb’s wall stands a plaster inscription adorned with raised Hebrew script.

The Story of Esther

Scholars have delved into Jewish religious texts, particularly the Megillah (Book of Esther) and the writings of Greek historians detailing the saga of Esther and Mordechai. These inquiries seek to shed light on the shrine’s occupants, notably the figure of Ahasuerus (Persian: Ahashverosh; اَحَشْوِروش), and have brought about important findings.

First account

In Greek mythology, Ahasuerus has been transliterated as “Asouēros”, and its narration is mostly conflated with depictions of Xerxes or Artaxerxes. The Book of Esther places the narrative forty years after the liberation and exodus from Babylon, which would make it during the reign of Darius I or Darius the Great. The text recounts a scene where, in a drunken state, the king summons his wife, Vashti, who refuses to attend the gathering.

Contrary to this narrative, some historians point out to other evidence and propose an alternate scenario where — enraged with his wife — Xerxes son of Darius the Great Achaemenid, selects Esther, a Jewish maiden, as Iran’s queen during royal festivities. Herodotus, the Greek historian, recounts Darius’s divorce from his first wife, Cyrus the Great’s daughter.

Second account: Purim

Another account states that Artaxerxes, the son of Xerxes, married Esther, a Jewish woman who was the niece of one of the courtiers, Mordechai. Thus, the Jews gained more influence in the court of Artaxerxes. Meanwhile, a powerful and influential courtier named Haman became jealous of the growing influence of the Jews and therefore managed to deceive the King into issuing a decree to massacre the Jews.

However, due to the unity of the Jews, especially the wise policies of Mordechai and the selflessness of his cousin Esther, this evil plot was foiled. In other words, a miracle called Purim took place.

Jews around the world have been commemorating and celebrating Purim for centuries under various circumstances. In the Persian dictionary, the word Purim is derived from the root “پور” (i.e. Pur) meaning “lot”. It is customary to fast for one day on the thirteenth day of the month of Adar, in memory of the three days of fasting of the Jews during that period. On the night of the thirteenth and the fourteenth day of Adar, the Scroll of Esther (the part on the events) is read from a special scroll, and the Purim celebration is held with lots.

Historical Study on the Second Account

Despite historical discrepancies regarding Xerxes’ identity, the Scroll of Esther promptly identifies the king as Ahasuerus and traces Esther and Mordechai’s paternal lineage to the tribes of Israel.

In Habib Levi’s work, the names from the Scroll of Esther are noted among the Babylonian deities.

Notably, during Cambyses’ rule, Cyrus the Great’s decree to build the Second Temple in Jerusalem was stalled. However, Darius the Great later issued a decree to resume construction, and by the sixth year of his reign, the temple was completed. This gesture earned Darius the admiration of the Jewish community. Ezra and Nehemiah, prophets and chroniclers of the Achaemenid era, documented Darius’ decree to finalize the Second Temple’s construction.

Furthermore, it is suggested that a queen was present during the decree’s issuance. Although Esther’s name is not explicitly mentioned, some believe it was probably her.

Based on insights from Bijan Asef, Dr. Kourosh Kiani, and Bina magazine.

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

Ester Mordekhai alley, the beginning of Abbas Abad street – taken from Hamedan museum archive

Year 1330 AD

The entrance door in the alley

Tomb of Ester and Mordekhai:

Visiting hours: every day from 9 am to 1 pm and from 4 pm to 7 pm

Friday afternoons and Saturdays are closed.

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

Spring 2012

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

The Tomb of Esther and Mordechai – Hamadan, 1966

Modifications to the Tomb in the Mid-1980s

In the mid-1980s, the Hamadan Cultural Heritage Organization, made the following changes while renovating parts of the Esther and Mordechai tomb:

- The old lock on the stone door, which with its exceptional principles and design could only be opened from the inside, was replaced with a large metal lock on the outside of the door.

- Some of the brick walls were painted, and the monochrome plasterwork paintings and inscriptions inside the tomb were also painted black to distinguish the inscriptions.

- The fence overlooking the main street, which was inspired by authentic Iranian tilework and took the form of the Star of David, was replaced with simple, light-profile fences.

From the notes of Yasi Gabai

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

1345 solar taken from Yasi Gabay archive

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

Hamadan spring 2012

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

1345 taken from Yasi Gebay archive

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

Taken from the Diarna archive

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

Spring 2012

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

Taken from the Diarna archive

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

Spring 2012

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechai- Hamedan 1345

From Neglect to Renewal — the Rebirth of the Tomb

Until 1970, before the implementation of the reconstruction and development project, the tomb appeared relatively dilapidated and hidden among countless ugly city houses and apartments. It was only accessible through a narrow, dirt alleyway, and the tomb’s façade was barely visible from the street. This prompted the Tehran Jewish Committee to commission engineer Yasi Gabi to design a renovation plan for the tomb in Hamadan.

From the notes of Yasi Gabai

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

Fascinating Aspects of the Tomb

One of the most fascinating parts of this old tomb is the stone entrance door, which is short. This door is crafted from a single, thick piece of granite and rotates within a recess filled with oil. The design of the lock is such that it is located on the inside of the door. There is no lock or even a handle on the outside. When the door is closed, to open it, the lock can be accessed through a hole that is drilled into it.

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

Taken from the Diarna archive

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

1345 taken from Yasi Gebay archive

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Historical Plaque at the Shrine’s Entrance

Respected pilgrim,

The shrine you are currently visiting is known as the Tomb of Esther and Mordechai. According to historical texts, it was originally constructed during the reign of the Mongol ruler Arghun Khan and was remodeled into its present form in 1402 AD.

The tomb on the right belongs to Mordechai, one of the prophets of the Israelites, while the tomb on the left belongs to his niece Esther. The latter tomb was built by a man named Enayatollah Tuysarkani.

The historical origins of this site can be traced back to the Achaemenid era and the reign of King Ahasuerus, who is believed by some historians to be identical to Xerxes I.

A Narrative of the Events:

Esther was chosen to be the queen, and Haman, the king’s chief minister, harbored a deep animosity towards Mordechai for refusing to bow down or pay homage to him, instead bowing only to his own God. Haman orchestrated a plot to exterminate Mordechai’s tribe. However, by the grace of the Almighty, who always protects and upholds His devoted servants, Haman’s evil intentions were exposed to the King, and on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar, Haman was punished for his misdeeds. To commemorate this event, the 13th day of this month is observed as a mandatory fast for the Jewish people, an expression of gratitude. The details of this story are recorded in the Scroll of Esther, which is read aloud in the courtyard of this tomb on this day.

We hope your pilgrimage is accepted.

The Jewish Community of Hamadan

A Monument from the Ilkhanid Era

The Tomb of Esther and Mordechai is a structure dating back to the Ilkhanate period (8th century AH) that was built upon an even older foundation. According to historical accounts, this tomb serves as the resting place of Queen Esther of Ahasuerus and her uncle Mordechai, who played pivotal roles in preventing the genocide of the Jewish people during their time. As a result, this site holds significant importance as one of their pilgrimage destinations.

Cultural Heritage Management of Hamedan Province

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Tomb of Esther and Mordechai – Hamadan, 1966

Evidence Indicates Replaced Caskets

According to the writings of historians such as Hertfeld, the original tombs are located much deeper below the ground level, and it is certain that the current caskets are not the original ones and have been replaced at least once during this period.

From the notes of Yasi Gabai

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

1345 solar taken from Yasi Gebay archive

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

Hamadan spring 2012

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

1345 taken from Yasi Gebay archive

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

Hamadan spring 2012

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

Taken from the archives of the Diarna site

زیارتگاه استر و مردخای

همدان بهار 2012

Shrine of Ester and Mordekhai

Hamadan spring 2012

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Name Mordechai

The name “Mordechai” in Hebrew translates to “little man”. This name was first mentioned in the Book of Esther, and he is one of the figures mentioned in the Tanakh.

Mordechai was the son of Jair from the tribe of Benjamin. He was exiled to Babylon along with King Zedekiah of Judah after the destruction of the First Temple in 597 BC. Upon arriving in Persia, he settled in the royal city of Susa and adopted his orphaned cousin Esther, the daughter of Abihail. Esther’s original name was Hadassah, but due to her exceptional beauty and charm, she was given the name Esther.

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

Outside the tomb, there is a special place for pilgrims to light candles.

Esther and Mordechai shrine – Hamedan 1345 AH

The synagogue’s interior ceiling features a layer of exquisite plasterwork, while its external architecture resembles a Star of David. This star-shaped layout holds and carries the ceiling and symbolizes “protection”. The Torah ark, known as “Hechal”, takes the form of a triangle with its apex pointing upwards, signifying ascent to the spiritual realm.

A skylight is installed above the Hechal to effectively reflect and direct sunlight into the space for daily prayers.

From the notes of Yasi Gabai

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

1345 taken from Yasi Gebay archive

A painting of the original casket, created by Eugène Flandin, a French traveler and archaeologist of the 19th century.

In the past, it was customary for pilgrims to light candles directly on the caskets and make their wishes. Unfortunately, due to negligence on the part of the custodians at the time, these caskets were destroyed in a fire.

Taken from the diarna archives

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

Taken from the archives of the Diarna site

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Shrine of Esther and Mordechaii

The Tomb’s Transformation

According to the writings of Ernst Hertfeld, a European historian and archaeologist, the original tomb structure dates back to 1602 AD, during the early 17th century under the Qajar dynasty. Upon the order of Jamal al-Dawlah’s mother, the façade of the main building was redesigned using a simple brick pattern inspired by the architecture of Imamzadeh shrines. This design features two small chambers and a dome that is visible from the exterior and forms the main ceiling of the tomb. A beautifully carved wooden casket lies over and beneath each tomb.

Taken from the diarna archives

The Tomb’s Transformation

According to the writings of Ernst Hertfeld, a European historian and archaeologist, the original tomb structure dates back to 1602 AD, during the early 17th century under the Qajar dynasty. Upon the order of Jamal al-Dawlah’s mother, the façade of the main building was redesigned using a simple brick pattern inspired by the architecture of Imamzadeh shrines. This design features two small chambers and a dome that is visible from the exterior and forms the main ceiling of the tomb. A beautifully carved wooden casket lies over and beneath each tomb.

Taken from the diarna archives

Artistic depictions of Esther’s story

The Dura-Europos Frescoes

The oldest existing painting related to the Book of Esther is found in the frescoes (wall paintings) of the ancient Dura-Europos synagogue, currently housed in the National Museum of Damascus in Syria. Built in 245 AD along the Euphrates River, this synagogue is believed to be one of the earliest synagogues with all its walls decorated in the style of Greek frescoes.

Among the depictions from the Book of Esther, one titled “The Triumph of Mordechai” shows Haman leading Mordechai’s horse. In another scene, titled “The Decree of Purim”, Ahasuerus is seen celebrating Purim.

Rembrandt and others

A black-and-white lithograph by the renowned French painter Gustave Doré captures Esther standing before Ahasuerus.

Giovanni Fatturi, a 19th-century Italian painter, presents Esther in his painting “Esther before Ahasuerus”, where she is held by her handmaidens and stands before the king.

One of the most famous paintings of Esther is “Ahasuerus, Haman, and Esther” by the 17th-century Dutch master Rembrandt, currently housed in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow.

Another Rembrandt painting titled “The Dismissal of Haman” also depicts a scene from the Book of Esther.

The beautiful work by 17th-century French painter Nicolas Poussin, titled “Esther in the Presence of Ahasuerus”, is another valuable piece of art showcasing the story of Esther.

The last two paintings mentioned are housed in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.74

A Question of the True Burial Place

Following the fall of the Babylonian Empire and the rise of the Achaemenids, the rulers of this dynasty established Shushan as their administrative capital, while Persepolis served as their ceremonial and ritual capital. At the same time, Ecbatana, or present-day Hamadan, served as another capital and the summer residence of the Achaemenid kings.

This means that the story of Esther, if not purely fictional, is likely to have taken place in the city of Shushan. This is one of the reasons why some historians do not believe the current tomb belongs to Esther. Another theory suggests that after the assassination of Xerxes, Esther and Mordechai fled to Hamedan fearing their enemies. They remained in Hamadan until their death and were buried there.

The Book of Esther: A Unique Narrative in the Torah

The Book of Esther stands out as one of the most captivating and engaging stories in the Torah. One of the key distinctions of the Book of Esther from the other scrolls of the Torah is the absence of miracles throughout the story. In addition, God’s name has not been mentioned even once throughout the narrative. This unique approach to storytelling lends the story a more realistic tone and places it among historical, rather than religious, books.

In essence, the Book of Esther presents another compelling illustration of the victory of light over darkness and the triumph of good over evil.

Esther in Jewish Art and Literature

The Book of Esther has captured the attention of many writers and especially master painters for centuries. French poet and playwright Jean Racine wrote the play “Esther” in the 17th century. This play premiered in Paris in 1689 and the original text is still taught in French schools as an exemplary work of classical literature. Many painters have also illustrated the Book of Esther, leaving behind masterpieces. A few examples will be mentioned.

To see 360-degree images (panorama) of Esther and Mordecai Shrine, please click

فارسی

فارسی